A Father's Day Reflection

My father didn’t get the life he wanted, but his fixation on what he had lost also kept him from embracing the life he had.

For Mother’s Day, I wrote a post about my mother and her life in a troubled and dishonest marriage, but no story exists in isolation or is one-sided.

My grandfather, Cornelius, my father’s dad, was an immigrant to Canada. A poor man whose livelihood came from subsistence farming in central Saskatchewan.

He married Katherine, a young German-Canadian woman, and soon they welcomed a son, John.

John was a celebrated eldest child and son, which mattered greatly to Cornelius.

John was his father’s pride. A son to help on the farm and eventually take over from his father.

Shortly, they added a daughter, Susan. Susan would help her mother around the house and with chores.

The family was exactly as Cornelius would have it.

Until … a few years later, Katherine became pregnant again. That baby would be my father, Jacob.

Jacob was unwanted.

My grandparents spoke Plautdietsch, a dialect of German-influenced by languages of the northern European lowlands where it originated.

My grandparents had a nickname for my father that roughly translates in English as ‘leftovers’, but in Plautdietsch is closer to an uglier word that roughly translates ‘compost’.

That was my father’s identity growing up.

Unwanted.

Unwelcome.

Until … in his early twenties, my father discovered a community that appeared to welcome and want him, to celebrate him.

He discovered the evangelical church and created a story about having overcome alcoholism and gambling addiction in an encounter with God while out alone in the field plowing.

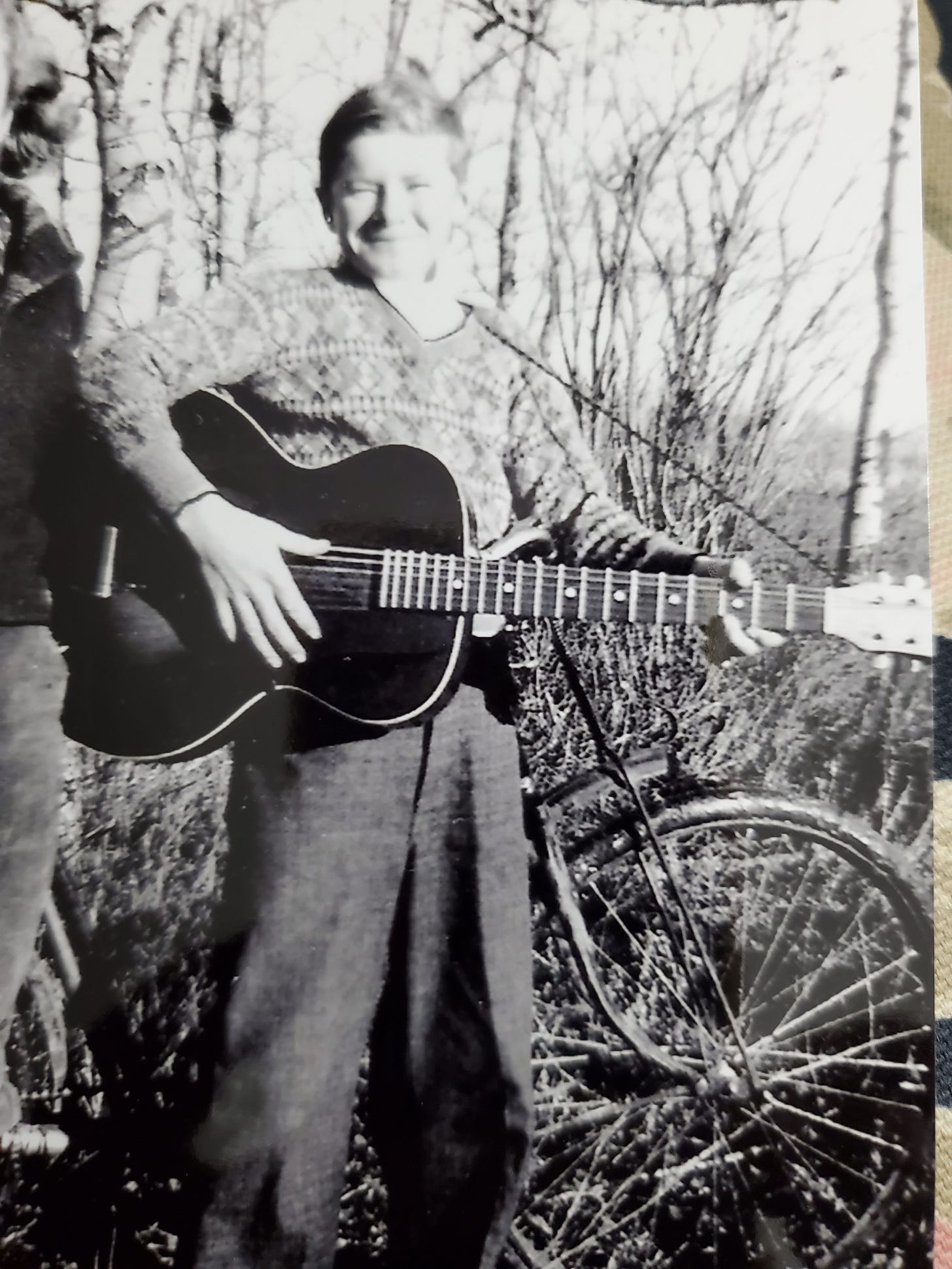

His day-and-night deliverance story, handsome looks, beautiful singing voice, and love of preaching (being looked up to, listened to, and respected) gave him hero status in the small pastoral training college he attended.

The leaders of the college gave no thought to anything deeper.

It never occurred to them that by celebrating his surface, a surface they helped to sustain, they were actively depriving him of an opportunity to know his deeper, true self, and by knowing himself honestly, to heal from the very real wounds of his childhood.

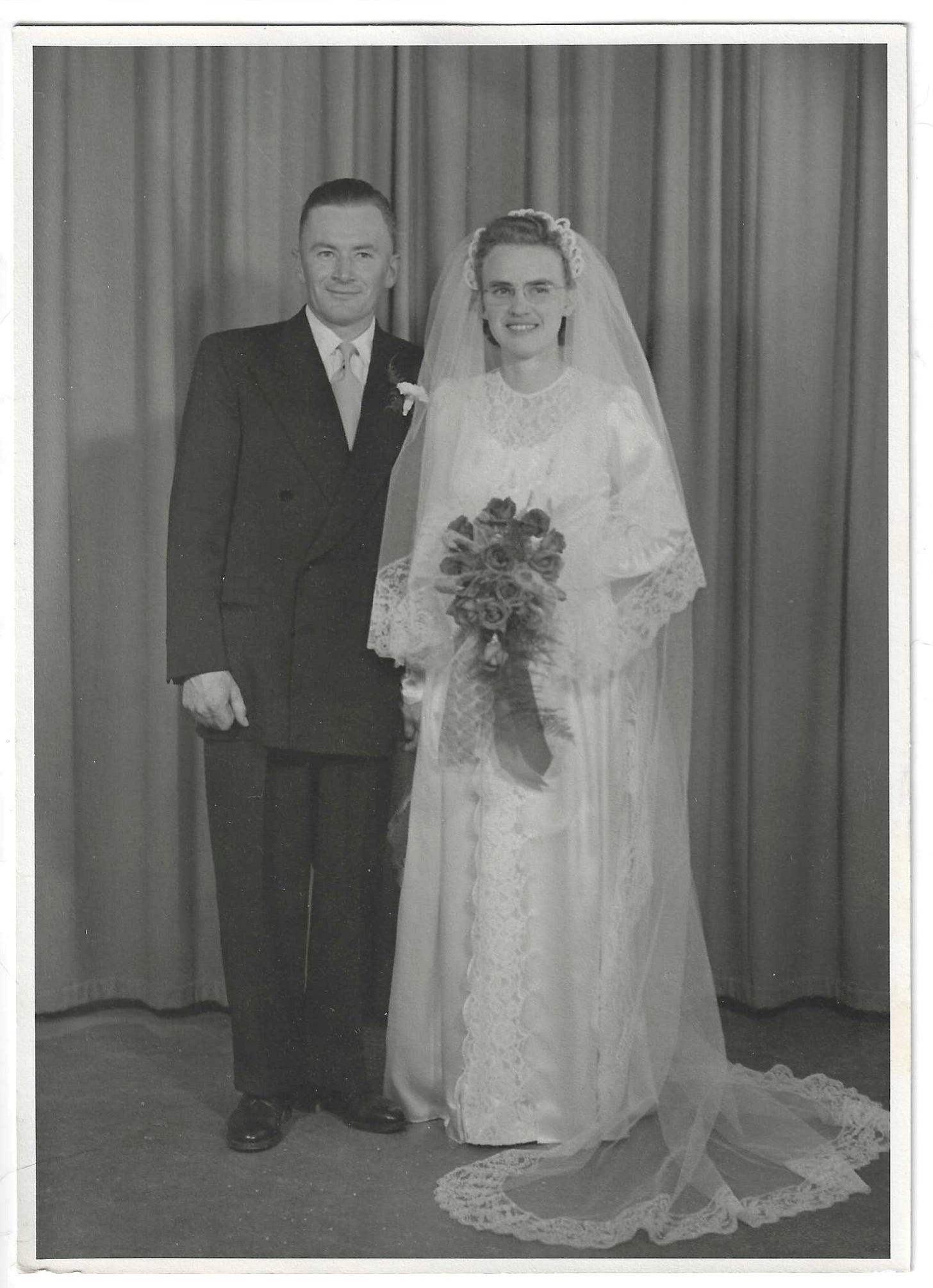

My mother lived in the small Saskatchewan town that was home to that pastoral college and met the deeply spiritual young man Jacob presented himself to be.

It’s hard to blame my father for his pretense.

I can imagine the pain of being so obviously and openly unwanted.

Or how good it must have felt to go from ‘leftovers’ to center of attention.

I can imagine how intensely my father wanted his ‘centre-of-attention’ persona to be real.

But it wasn’t.

And while he could maintain it in public at times, he could not maintain it for long, and certainly not with the woman he married.

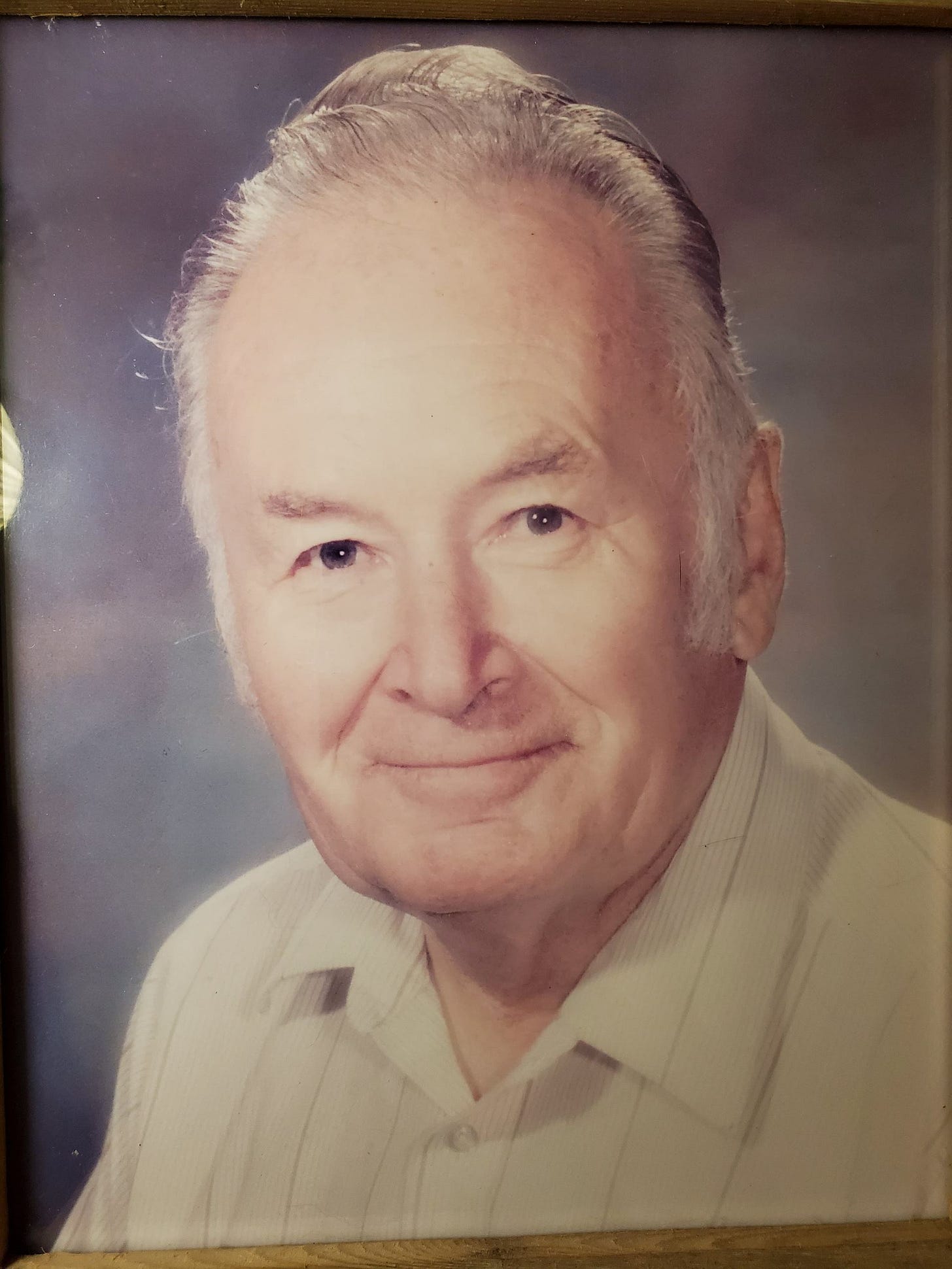

When my father was dying, he lamented ‘never having the life he wanted’ and furiously blamed my mother for that loss.

But the life my father wanted was the life of his persona from the pastoral college.

It wasn’t real and never could be.

A much deeper tragedy was at play, though.

My father didn’t get the life he wanted – the life of that spiritual hero that everyone admired – but his fixation on what he had lost also kept him from embracing the life he had.

As I wrote in my Mother’s Day post, there was a time in my childhood when my father decided to leave my mother and his children, and I can imagine that part of the reason was our failure to hold him in the same esteem as the church college.

When my father was dying, he railed at my Mom one day about how she had embarrassed him when she had asked him to say table grace over meals when we had company.

When it was just family, my father would pray a simple poem-prayer:

Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest (as a teenager, my snarky inner voice would add, ‘just don’t stay too long’)

And bless what thou providest, asked,

Amen.

But when company came, my father would pray what felt like more ‘real’ prayers over dinner, and apparently, having to summon up a prayer in front of others was ‘embarrassing’ for my father. Embarrassing because he was trying to do something he had very little practice with (talking openly and honestly with God), and therefore didn’t feel at ease doing.

When I think of my dad, I mourn the life of pretense that he felt he had to live. I mourn for him the loss of love and welcome and celebration that he deserved as a child. I mourn that the place he felt the most ‘belonging’ (his pastoral college) was a place that wanted to use him, not help him heal or grow.

It’s awkward and ill-fitting to try to mourn my relationship with him. My father was unwilling to accept or forgive my struggles with mental illness. He felt that I could ‘choose’ to do better. Worse, he saw my illness as reflecting on him. Having a daughter with an untreated psychosis made him look bad, and for my father, even feeling like he might be losing the admiration of people around him was unbearable psychic pain.

My father could never accept the one gift that would have healed him of the brutal wounds of his childhood: he could never accept himself. But that meant that my father could never accept anyone who didn’t celebrate and polish his surface image.

And that meant me.

It’s ironic that my father – who experienced such unwelcome as a child, son, and sibling – was never able to accept his own children in the fullness of their personhood and personality.

I mourn for my father that he never felt the welcome and belonging we all deserve.

I mourn for him the driving need he felt to manipulate acceptance out of others.

I mourn for him that his spirituality was a shiny exterior that he used to gain acceptance, not a core relationship with the Divine that empowered him to love the Divine, to love himself, and to love others and the world around him.

I mourn deeply that my father left this world filled with venomous anger for ‘not getting the life he thought he deserved’ when a beautiful life lived in his house, eating at his table, catching fly balls in the park with him on Sundays, skiing and skating with him on winter weekends.

My father’s wounds shaped his entire life, in part because his church encouraged him to have only ever ‘overcome’ his wounds, and in part because my father could not imagine being loved and welcomed in his wounded state; and because he couldn’t imagine being loved in a wounded state, my father could not love anything he saw as less than perfect – including himself, his wife, and his family.

On this Father’s Day, I remind myself of the power of welcoming all of life, all of my life, just as it is and as it comes. Which does not – really does not! – mean that all of life is pleasant and lovely, or even that we need to pretend that all of life is pleasant and lovely. Life can be hard, hard enough to wound us, and at times break us. But health and hope and a genuine happiness that transcends the vagaries of circumstances are found in that acceptance. Not in a passive acceptance that collapses in its pain waiting for some miracle to make it all go away, but in an active hopeful acceptance that understands that taking the next step requires firmly planting both feet on the ground beneath us.

We are here.

We are wounded in many different ways.

And here is where we need to accept our Selves, to know that the Divine – God, the Universe, Spirit, Goodness, Life, choose the name for works for you today – accepts us without condition, celebrates us and cares for us, and that we have within us gifts of acceptance and welcome and care to offer to those around us.

I don’t know anyone who can honestly say that their life has worked out exactly the way they planned or hoped and that it is all good. It is an impossible hope.

But I do know people, and I work every day to be one, that find, right in the life they are living, the healing, hope, and purpose that gives meaning to our hours, days, and decades.

I mourn that my father died feeling that the life he wanted had been stolen from him.

I honour his memory by trying to choose more often than not to accept the life I have, to want the life I have, and to live that life with gratitude, hope, and Love.

Thanks for your honest words of mourning and remembering your dad and your inspiring desire to accept the life that you have, finding Love and Grace embedded right in the middle of it all.